HIDE & SICK

Category: Apparel

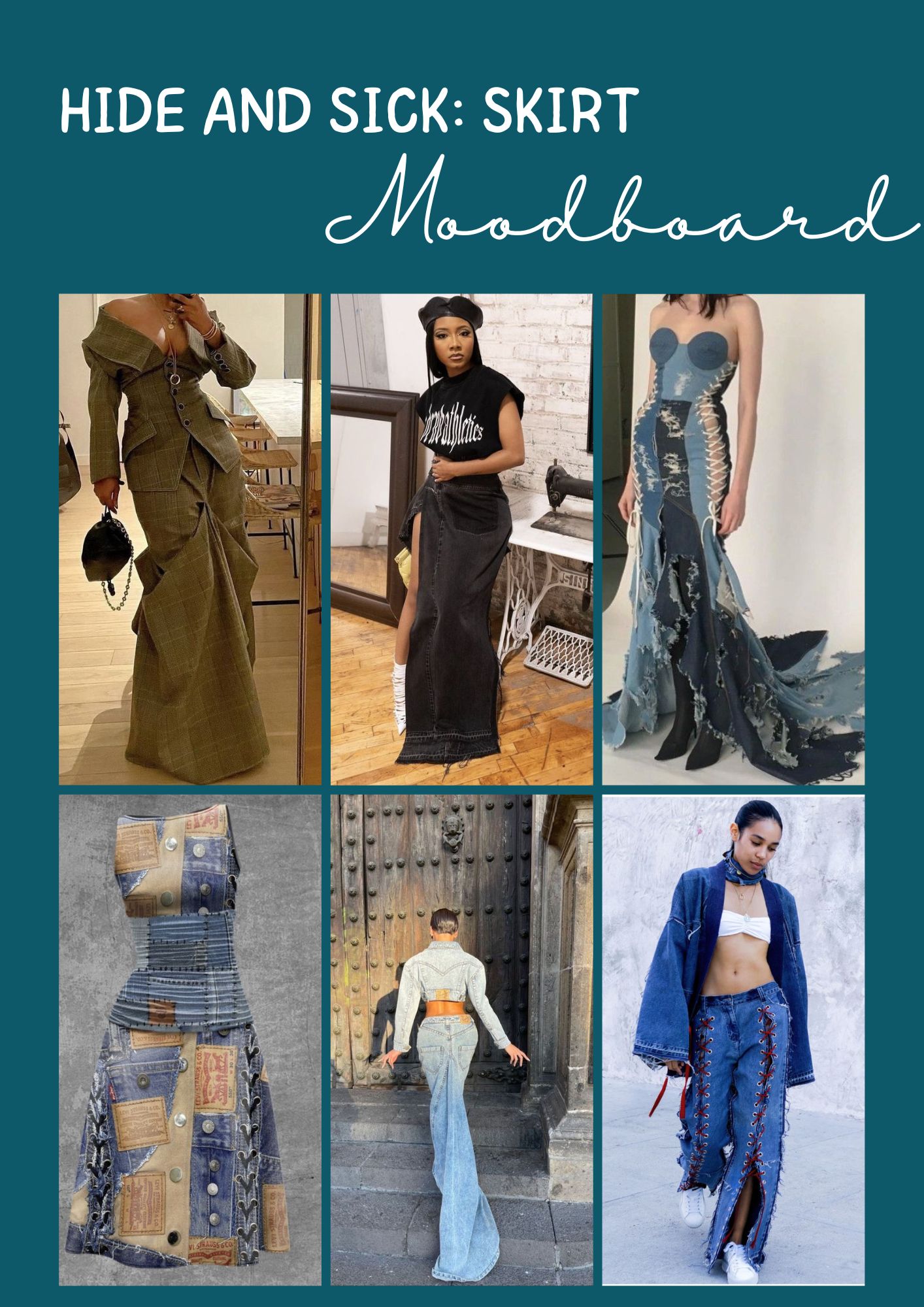

HIDE AND SICK. THE TITILING. The title of my project Hide and Sick to me is where the world of leather fashionary and craftsmanship meets the world of playful creativity. I named my project Hide and Sick because of how the two words cleverly play on each other, encapsulating how HIDE needs to get CURED or TREATMENT for use. The word sick also came off to me as intriguing as a Gen Z slang how we’d say ‘that’s sick’ to show the coolness and impressiveness of something hence a punning on the meaning. GENERAL BRIEF This two piece design sketch blends the timeless elegance of a tops and bottoms piece with a touch of both traditional & modern sensibility. FLEECE JACKET The Sleek silhouette of the jacket incorporates the Maasai beads that have culturally stepped foot after the other in every year of the past centennial, patterned on leather which is settling at the middle bodice. The upper bodice and lower parts of the bodice are made of denim, the upper bodice carrying a cap and 'veil' that is attached to the shoulder parts of the back with press buttons which allows for the cap and veil combo to also fall as a hoodie would. This cotton denim fabrication module, hero-worships farmers from the Bantu community specifically the Akamba tribe. LEATHER SKIRT. BEADS AND GLASS ADORNMENT ON SKIRT. The bottom skirt is a harmonious blend of elegance and edginess. Crafted from leather, I aimed at my design swaggering a sleek and form-fitting silhouette that accentuates curves with every step. What sets this design apart, are the ceramic clay beads and the exquisite glass bead crystals, airy hanging from random parts of the upper skirt, catching the light and adding a touch of glamour to the creation. METAL ADORNMENT ON SKIRT Rooted in the rich heritage of the Agikuyu community of Kenya as well, this leather skirt design as well celebrates the artistry of traditional blacksmithery here in Kenya. Each brass metal button adorning the skirt, pays homage to the intricate workmanship of Agikuyu blacksmiths, who crafted utilitarian and ornamental metal pieces for their community. These buttons are strategically placed randomly as well on the upper parts of the skirt, adding a touch of authenticity and cultural heritage to its design and enhancing a feel of timeless tradition and the spirit of craftsmanship passed down through generations. THE CULTURAL AMALGAMATION IN THE DESIGN SKETCH. Personally coming from three tribal bloodlines here in Kenya(Maasai, Agikuyu and Akamba; my dad being halfcast Maasai, Agikuyu and my mama from the Akamba tribe here in Kenya), I wanted my design to appreciate the branch fruits of all my tribal roots. I therefore below explain, how each impacted my design sketch. THE SMITHERY STORY OF THE AGIKUYU FROM MINED ORES AND THE PROCESS OF CASTOR OIL MAKING THAT WAS USED TO CLEAN AND ALSO SOFTEN LEATHER IN THE AGIKUYU COMMUNITY. One of the most famous Gĩkũyũ folktales tells the story of the blacksmith, (Mũturi) who had left his pregnant wife and gone to work in the smithy a long way from home. The famous Agikuyu Muturi story link: https://youtu.be/0GyvNf7qhuI The blacksmiths among the Gĩkũyũ tribe organized themselves and operated in a lodge located in a secluded area known as Kiganda. Extracting ore from the depths of the earth, believed to be from the hands of the ancestors, Ngomi, and Mother Earth, then skillfully crafting it into spears, knives, swords, and agricultural implements, was considered a form of ancient sorcery that was revered with the same reverence and trepidation as Ũgo, or wisdom. The practice of blacksmithing, known as Ũturi, among the Gĩkũyũ was more of a sacred tradition and cult rather than a mere practical skill, as the items created were essential for the functioning of their society, rather than being motivated purely by profit. The process of innovation and crafting was strictly regulated, with new members of the blacksmithing cult undergoing a complex and costly initiation that imposed restrictions on their creative endeavors. This strict control ensured a harmonious society that was resistant to the dangers of unchecked technological advancement driven by consumerism and greed. Many of the rituals and secrets associated with the blacksmithing cult remain shrouded in mystery to this day, known only to a select few practitioners and respected elders. Castor Oil was produced by roasting the seeds, still in their shells, on a piece of broken pot called rugio, similar to the process of roasting peanuts in a frying pan. The roasted seeds are then crushed into a paste by beating them in a leather skin garment, without hair, using a stick. The paste is transferred into a pot called Nyungu, where water is added almost to the brim. This mixture is then placed on the fireplace, known as riko, and cooked for several hours. The oil rises to the top of the water and is carefully drained into a calabash before being transferred to an oil storage container called Kinandu. The oil is collected in two grades - the first grade is a clean extra virgin oil, while the second grade containing some crushed shells, is used for softening leather clothes and carrying straps called mioho and mikwa. These leather products are left to dry in the sun, resulting in a soft and shiny finish. The grade 1 oil is reserved for skin toning, hairdressing, and ceremonial purposes. RELATED FUN FACT Leaving a pot of castor oil cooking unattended was considered taboo due to the highly flammable nature of the Gikuyu woman's dwelling (grass hatched huts, Nyumba), making the oil production process a high-risk activity. MAASAI BEADS: HISTORY, SYMBOLISM, and CULTURAL REPRESENTATION. The Maasai people of Kenya and Northern Tanzania have a long storied history that is woven with the traditional art of beadwork which dates back centuries, evolving from use of natural materials like seeds, shells, and bones to the fusion of glass beads from European and Asian traders along the Swahili coast in the 19th century. These glass beads, quickly became highly prized by the Maasai for diverse color palette and durability that came with them. Maasai artisans, particularly women, sharpened their skills in beadwork, creating intricate patterns and designs that reflected the richness of Maasai culture and traditions. Color Symbolism: 1.Red: Symbolizes courage, bravery, and the blood of the Maasai warriors who defended their communities. 2.Blue: Represents the sky, divinity and protection, evoking the vastness of the African landscape and the spiritual connection between the Maasai and the heavens. 3.White: Signifies purity, health, and harmony, embodying the spiritual purity of the Maasai people and their close relationship with nature. 4.Other Colors: Each color holds its own significance, from green representing the earth and fertility to black symbolizing unity, solidarity,color of the people, and the collective strength of the Maasai community. Pattern Symbolism 1.Beadwork patterns often depict elements of nature, Maasai mythology, and spiritual beliefs. Geometric designs may symbolize the interconnectedness of all living beings, while animal motifs reflect reverence for wildlife and the natural world. 2.Certain patterns and designs are specific to particular clans or families, serving as markers of identity and lineage within the Maasai community. Cultural Representation of Maasai Beads: Social Significance: 1.Beadwork serves as a visual representation of Maasai identity, social status, and lineage. Different beadwork designs and colors may denote a person's age, gender, marital status, clan affiliation, or social standing within the community. 2.It is prominently featured in various Maasai ceremonies, rituals, and rites of passage childhood to adulthood, marking important milestones in individuals' lives. Economic Importance: 1.Beyond its cultural significance, beadwork also serves as an economic activity for Maasai women, who are primarily responsible for its creation. Many Maasai women engage in beadwork as a source of income, producing jewelry, ornaments, and decorative items to sell or trade locally and internationally. 2.The sale of beadwork provides women with financial independence, reduced feminization of poverty and contributes to the overall economic well-being of Maasai communities. Today, Maasai beadwork has gained international recognition for its beauty and cultural significance, with many artists creating contemporary designs that blend traditional techniques with modern aesthetics. Through their intricate beadwork, the Maasai continue to preserve their traditions and share their unique artistic expressions with the world. TRIBE FUN FACT As a right of passage to warriorhood promotion among the Maasai youth, one was required to show bravery by hunting down dangerous wild animals, most of the times fighting down a lion and killing it to show being heroic and your ability to fight for the community. THE BACK STORY OF THE BEADS TO BE USED. The Kazuri Beads organization was founded by a passionate woman by the name Susan Wood of parents from American Origin. Her story is so important to me as she was African through and through and lived variously at the foot of Mt. Kilimanjaro,which is also where I grew up and have lived up to date with my parents.The name "Kazuri" means "small and beautiful" in Swahili, reflecting the exquisite craftsmanship of the handmade beads produced by the women artisans. Susan's mission was clear: to create sustainable employment for single mothers and disadvantaged women, which allowed these women to support themselves and their families too with ethical dignity and a sense of pride in their works. The story of Kazuri Beads began in a modest workshop in the year 1975 in Karen, Nairobi after Susan and her husband relocated to start medical services here in Nairobi, the husband being a medic. Here, Susan employed two less fortunate women from the area and realized there were more women that needed employment.She then gathered a group of talented women from the local community, mostly single mothers. These women had faced hardships and challenges in their lives, but with Susan's helpful guidance and support, they discovered a newfound sense of purpose and belonging in their lives through their crafts. Using a special clay from the foot of Mt. Kenya, the women began shaping and hand-rolling beads of various shapes, sizes, and painted them with different colors mainly using African motifs. Each bead was a labor of love, alloyed with creativity and determination of the women who created them. Word spread about the unique beauty and great quality of Kazuri beads, growing the demand for their products, leading to a quick expansion and thriving of the organization. Kazuri Beads did not only stand out through their truly special and eye catching work, but also through the story behind them, changing everything about a simple string of beads.. Each bead carried with it the story of the woman who had crafted it then – a story of resilience, strength, and hope. By 1978, Kazuri had a market, first in Britain, then the US. They had agents who were buying and selling the brilliantly-colored beads along with a video to prove the fact that they were indeed hand-made by the single mothers, the fact that this was a growing cottage industry, and that Kazuri also provided much- needed medical care(this was easy as the husband was a medical practitioner),access to education and fair wages for these women. Through their artistry, these women found a voice and a means to support themselves and their families. Kazuri Beads grew further a symbol of empowerment and social change since then to date, inspiring other women in Kenya and beyond to pursue their dreams and break free from the cycle of poverty. THE AKAMBA COTTON PLANTING AND RITUALS RELATED TO ACHIEVEMENT OF GOOD HARVESTS. My inclusion of denim to my design sketch was highly influenced by my grandmother’s cotton planta tion in my upcountry home, that has slowly lost production rate over the years compared to when I was a small kid visiting. Cotton farming was not only an economic activity then, but also a cultural practice among the Kamba, with traditional songs, dances, and rituals associated with the planting and harvesting of cotton being done. Cotton fabrics were highly valued and used for making ceremonial attires, and household items, reflecting the cultural identity and craftsmanship of the Kamba people. It was such a special fashion moment to me when younger, knowing I was putting on a fabric from the plantation of my people as the companies my grandmother would sell to would bring back few rolls of already fabricated cotton for her daily tailoring uses. Blessing of Seeds: Before planting cotton seeds, the community gathers for a ceremony to bless the seeds and invoke the spirits of ancestors for a successful planting season. Prayers and offerings are made to ask for fertility, protection from pests and diseases, and favorable weather conditions. Planting Songs and Dances: As the seeds are sown into the soil, the community may engage in songs, dances (in the clan I come from, they call these dances Kilume), and chants to celebrate the beginning of the planting season. These rituals serve to uplift spirits, instill a sense of unity, and express gratitude to the land and ancestors. Sacred Offerings: Offerings of food, beverages, and symbolic items may be placed at designated sacred sites or shrines to honor ancestral spirits and seek their blessings for a fruitful harvest. This may include traditional foods, such as grains, fruits, and livestock, as well as symbolic objects representing abundance and prosperity. COMPETITION THEMES FEATURED IN THE TWO PIECE DESIGN SKETCH. INNOVATION & CREATIVITY- the attachment of the headpiece and veil to the bodice of the jacket to make the jacket one piece to me was a breathe of fresh air, Innovating a piece that will serve diverse purposes. The head piece can be matched with different other outfits and still give a major serve leaving a design that also allows the fleece jacket to stand out on its own but still maintain an aesthetic. For the skirt, I would have never imagined the world of pottery meeting the leather craftsmanship world, and I am certain most people would not too; this is the specialty and fashionary amusement statement of my skirt design. RECYCLING AND REDUCTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL FOOTPRINT- the glass beading designs are from an organisation that recycles glass bottles whilst smelting new ones. The Maasai culture in beading also uses recycled plastic yoghurt cups as bridging in between the beads and recycle grain bag threads as the beading threads. COMMERCIAL VIABILITY- My first sketch design(uploaded as well) was originally to make a coat from untanned outside parts of the hide, but I later changed it to the final design fleece jacket for purposes of easier commercial appeal and also considering that beading could produce as many designs patterns as there could be including animal patterns, geometrical and flag patterns. This gave the design more platform for manipulation enabling product market diversification. For the white leather skirt, the design would still stand appealing even without the ornamental details brought forth by the metal buttons, glass and ceramic beadings just from it's silhouette. FUSION OF TRADITIONAL AND MODERNITY- some of the buttons to be use on skirt are engraved with ancient forms of writing eg Hieroglyphics as these buttons are of Hong Kong Origin, made in 1990.(I thrifted them hence unique in style although pseudo ones, from my research, are being sold in only one shop on Etsy). I added them to the design in remembrance of Egyptian lexicographers J.J Barthelemy(1716-1795) and De Guignes (1721-1800) among others who dedicated their years to translate the hieroglyphs to alphabets and writing the first Egyptian dictionary that has personally helped me in my just recently started journey of reading the Rosetta Tablets from ancient Egypt. The Maasai beads on the fleece are also a fusion of early craftsmanship and recent history as the Maasai started off with bones & seeds but are now using glass beads from the 19th century for most of their works.

Copy URL

Copy URL

Login to Like

Login to Like